FIELD REVIEW: South Asia

Introduction

Meenakshi Thirukode

______________________________________

Abstraction De-Constructed through the Lens of Post-Colonialism

Achia Anzi

Grasping at the Untold

Jyoti Dhar

Kumar Vaidya: Through the Lens of Erasure and Invisibility

Meenakshi Thirukode

Yasmin Jahan Nupur: Dancing in the Non-Spaces of Performance

Zeenat Nagree

The Poetics of Absence and Presence in Parul Gupta’s Art: A Case for Revisiting Theories and Histories of Abstraction

Somak Ghoshal

The Immediacy Of Rejection: Music, Curation, and Sincerity in New India

Rana Ghose

______________________________________

About the Author

Rana Ghose

is a curator, economist, writer, and filmmaker. He steers the REProduce collective, a group of twelve musicians that mostly perform in the context of electronic music production. His current focus is REProduce Listening Room, a series of interventions in non traditional spaces that engages with music and video in modular, sequential plays – taking advantage of the aesthetics of spaces as varied as former mills, bakeries, and hotels and producing them into five hour embedded experiences where up to eight different performances unfold. His doctoral research was on risk constructions in a regulatory context, and the underlying dynamics of how we explore uncertainty. The theoretical framework of this research underpins his explorations in performative spaces and the capital intensive model that generates arenas that may or may not suit the wide range of artistic expression that a country like India increasingly generates, and how patrons and sponsorship models interact within the uncertainty that the resultant incentives present. He is based in New Delhi, India.

The Immediacy Of Rejection: Music, Curation, and Sincerity in New India

Rana Ghose

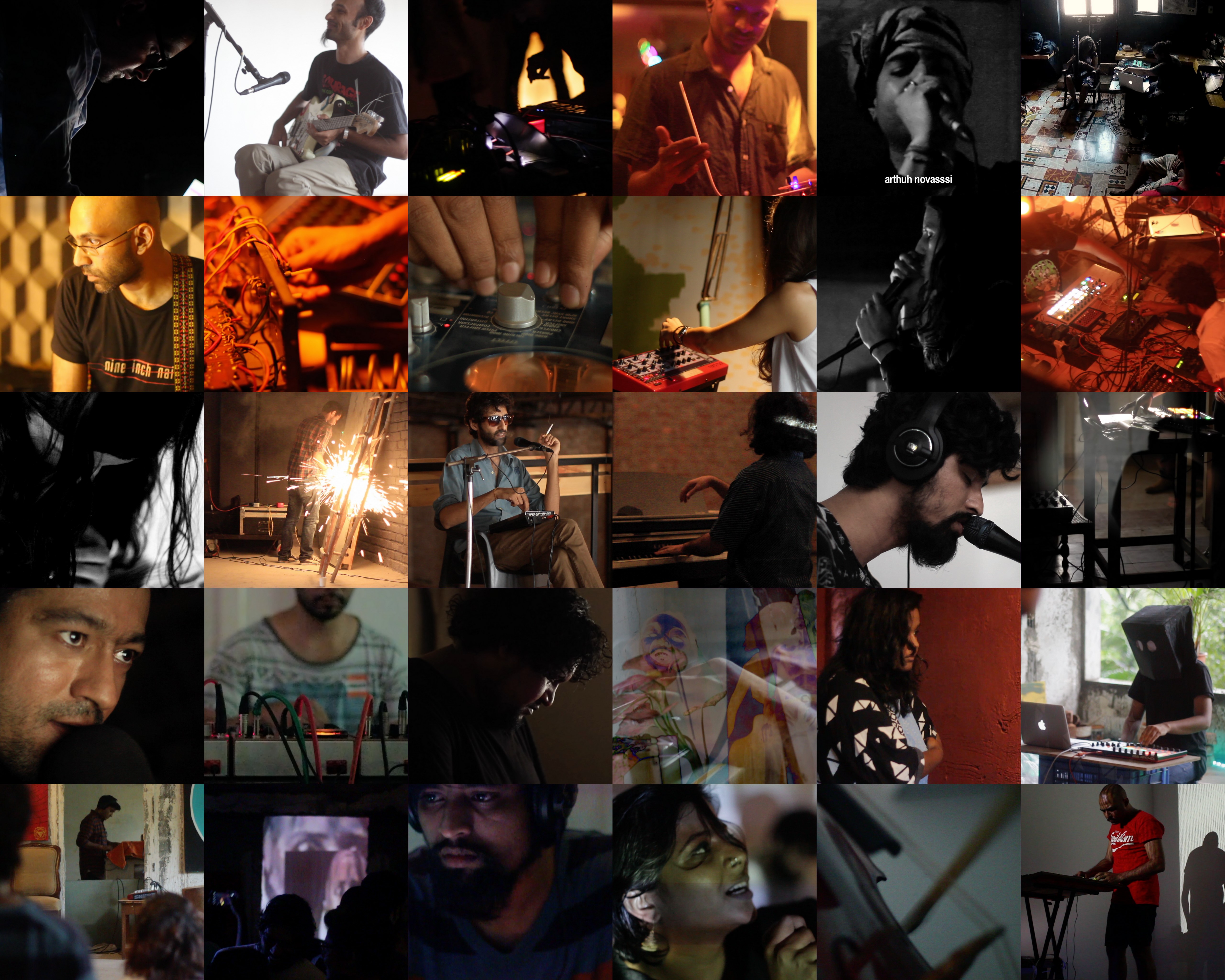

REProduce Listening Room, 2016. Photo Courtesy of Rana Ghose

Pop culture tropes in the South Asian context have, post independence, been steered predominantly by two incentives; an identity premised on visual narrative via Bollywood, but perhaps more than anything else, the goal of reaching out as wide an audience as possible. Scale has always been the first and foremost objective, with risk taking being seen as a burden as opposed to an opportunity. The role of the film industry here falls outside the remit of this piece and has been addressed well elsewhere. The second, however, has not, and in light of the rise of what has been termed “indie” music in the region, would benefit from some consideration.

The term “indie” as a variation on “independent” is somewhat of a misnomer. The implication of the term is to describe music outside the realm, and the financing in particular, of Bollywood. The irony – and danger – is that, to date, this emerging culture has fallen prey to another model; corporate sponsorship and subsequent cultural appropriation for profit and brand loyalty pandering.

The ultimate outcome of this relationship between firm and artist has resulted in a sort of stunted, yet rapid, emergence of a generation of artists playing to new and engaged audiences. While the older tradition of college festivals as a means to disseminate “rock” music in the nineties was certainly a veritable rite of passage for many currently in their late twenties and thirties, India seemed to leap frog from that model into a new arena. The restopubs of urban India have been the de facto arena for showcasing live music, and as such they have played a very important role as a means to both allow musicians to grow, but also to inspire many others to play music to a public.

But what are the implications of this? What happens to pop culture when the brokers of audience and artist are not taking financial risks apart from those that underwrite the selling of food and beverage? What if a new, younger patron of music feels less drawn to nocturnal events where alcohol, as opposed to the experience of listening, wanes as an incentive? Can an artistic narrative coalesce away from this model as a sort of implicit rejection of the status quo and if so, what is the long term viability of this narrative?

In the context of this new South Asian musical narrative, there are two distinct generations to consider. First are a cadre who are now in their mid to late thirties. This generation likely began to make music at the turn of the 21st century, forged on a combination of nascent scenes in Delhi (i.e. the Talvin Singh inspired “cyber mehfil” [1] parties on the outskirts of Delhi in the late nineties) and Mumbai (i.e. the first iteration of the Bhavishyavani Future Soundz [2] collective). Between these two geographic poles a generation came to grips with what may be the great unifying factor in this current context of new musical performances: electronic music production. Within five years, internet connectivity became more widespread, and with this came the onset of social media – MySpace and talk forums in particular. These arenas served to connect people in different parts of the country via allowing their music to be heard and shared more widely, and within the space of forums, unedited criticism (and allegiances) to be shared and forged. It was, in essence, a sort of informal arena for assessment of this new music.

Yet the real catalyst here in terms of how this music moved out of the bedrooms of producers and into the arena of a public was the wide scale entry of the sponsorship model. If Sunburn, a large scale electronic music festival that debuted in 2007 and has since grown to accommodate over 350,000 attendees annually, was the template to assert how a beverage partner can enter the entertainment space in “indie” India, it was the smaller scale analog of this – the restobar – that brought this to the urban spaces.

By 2010, in cities like Delhi, Bangalore, and Mumbai, pockets began to form where entrepreneurs realised there was money to be made from the sustained presentation of “indie” pop culture. Unlike in other markets globally however, there was never an intermediary step. Typically, and historically, pop culture brokerage in the context of music would be fostered by an entity – typically a record label – that would take the risk of signing an artist and getting him or her the right PR opportunities to buffer taste making, with the aim of recouping their speculative investment on record sales. The underlying model was embedded in a certain risk.

In India however, the risk model surrounding “indie” music was never taken on by a third party. In fact, terming it risk might not even be appropriate.

Countless marketing studies of India focus on one aspect of the demographic nature of the country; the seemingly infinite number of young 18-22 year old people; the fabled “millennial”. This mythical creature – brand malleable, with disposable income, and connected at all times to social media – is the holy grail of an MBA just entering the office of a firm focusing on how to leverage this new pop culture into hard sales. The recipe appears simple: partner with an artist management agency, allow the restobar to stock the alcohol at a discounted rate, plaster the venue with marketing detritus, and ensure that whatever artist plays can bring in people to promote the product and “brand experience” to. Within such a model, and by construction, risks that actually forge new paths musically are not factored in, and due to a simple fact: forging new musical paths is not the ambition of a marketing executive. Their remit is simple: maximise the brand optic, and ensure that as many people – whether welcome or otherwise – see it as possible. From their perspective, the artist gets paid, the venue sells food and beverage, and their brand optic is met. Find the right artist agency – one manager has expressed that his objective is “to find the path of least resistance” – and the deal is sealed.

While there is nothing inherently flawed from a business perspective of this model, the business of pop culture is a fickle thing. The crux of pop culture permeation reflects the relative ephemera of our own lives. Our decisions are always guided by the spectre of an uncertain future. That uncertainty propels a sort of loneliness, and ultimately makes us want to belong to a community of sorts. In the pop culture space, the defining factor of how one feels an attraction to a particular community – ethereral as it may be – is that ever elusive factor: to be “cool”.

Historically, most pop culture movements were always premised on a small number of committed individuals who began to organise amongst themselves to create a community of their own – the beats, dadaists, drum and bass, punk rock, zine culture – all of these examples started small, sustained themselves via a mix of enthusiasm, hard work, and commitment, and then grew and tipped over into the mainstream – or fizzled out. But for those that did not fizzle out, the inevitable occurred. If these individuals were “simply doing their thing”, post a certain point of regular interventions the curiosity of those on the outside began to tip over. It’s a mere reflection of that base instinct – to belong – and if those previously on the “outside” did not initially understand what exactly the big deal was, there was – and is – an innate gravity to want to understand, or at the very least, to pretend to understand in order to gain access. These communities would then grow, and would then either attract investors and grow, or plateau on the basis of an ideology and remain.

In India, we are now almost ten years into a scaled model of “indie” pop culture brokerage premised on the model of sponsorship financing, or “cultural” grants rooted in the soft diplomacy space, sourced from the embassies of developed economies. Since the deregulation of the alcohol industry and larger, more aggressive presence of firms looking to enter the pop culture brokerage space, we are now approaching a certain level of familiarity amongst patrons of what exactly it means to go out to see a show. One could argue that this familiarity is spilling over into a saturation point, and premised on a simple argument: if the generation of late twenty year olds and older grew up in a context where mobile internet access was not deemed something akin to a right, this generation of millennials grew up assuming the internet was normal. And as such, the cultivation of their tastes, expectations, and perhaps most importantly, the iterative identity politics of what it means to be “Indian”, has been informed by a seemingly infinite pool of references.

Unlike the previous generation, their making this music is not informed by bootleg cassette tapes sourced from electronic markets, visiting relatives from abroad, or whatever tie ups HMV, Times Music, or other regional distributors may have had with their international counterparts. Their references are far richer, and their going to a venue to see a show presents a very different spectre of engagement. They are keenly aware of the underlying context of why these places exist, and they are very aware that more often than not it is not for the sake of the music, but rather a marketing exercise to bait their tastes. As such, this generation is effectively empowered to reject.

It is this rejection that lies at the core of what we are seeing today in urban India. Since the onset of the restobar model, the underlying incentive was to simply allow for free entry to an event. Yet most people are more than willing to pay for a live music experience, and if anything, are waiting for it. The restobar circuit as it currently exists now is dominated by around six agencies [3], many of whom mostly focus on presenting either the artistry they formally represent, or producers from outside India. It is of course no surprise then, that patrons are reaching a point of saturation.

This culture of rejection is, of course, the best thing that could happen to this new industry. In rejecting, what we are seeing is a desire to hear music not brokered by these parties, and even more exciting than this, for musicians to find and produce their own spaces, to charge entry at the door or find alternative means to generate revenues to take on the logistics of production themselves, and ultimately, to suit the emerging demand that an essentially untapped demographic presents. In doing do, these parties are afforded complete independence – not the ruse of “indie” – but actual risk, absorbed by the value of ones own decisions, and accountable solely to themselves. The stakes are real, and in these arenas, actual development and change has the capacity to occur, based purely on finding partnerships with like minded people outside of the realm of sponsorship models and agency allegiances. In 2016 in particular, more and more similar minded, independent organisers are entering the fray, moving away from the sponsorship model and taking on these risks. [4] It is within these spaces that inspiration exists, and where real, long term change is forged. This is not a theoretical assertion.

Guided by the observations that this short essay has presented, this author has produced, at the time of this writing, fifteen events since February 2016 that are directly premised on the dynamics discussed here. As a direct response to these observations, REProduce Listening Room [5] has showcased over thirty artists over twelve different venues across six cities. These events begin in the afternoon on a Sunday, following the course of the setting sun over five hours and six acts until nine in the evening, far removed from the assumption of nocturnal revelry as the only arena for musical engagement, combining design, the visual medium, and sound into a holistic, unique experience. The events merge both established artists who have been performing for over fifteen years with those who have never played before at all in a seamless intervention, free of agency exclusivities, generating revenues purely by ticket sales and by retail interventions in the form of “pop up shops” and locally produced merchandise. In doing so, and based on many conversations the author has had with these patrons, this new generation seems to have found an arena that they are instinctively drawn to; one not premised on an “entertainment” model, but rather on a sincere, uncompromising musical experience rendered sustainable by careful curation and relevant financing.

What we are seeing is an emerging capacity by a generation to navigate global trends via not merely aping pop culture tropes as was often the hallmark of the past, but adapting these tropes to suit their local realities. To state this as an act of “defiance”, as some observers have suggested [6], may be extreme. However such an assertion is telling of the underlying frustration that characterises the existing model of showcasing music in the region. Less embedded in that antagonism is something more positive; there is clearly something akin to a movement with a telling momentum that is emerging, and for all the right reasons. In a pop culture space, the lifespan of pandering to the lowest common denominator for financial profit is bounded; alternative models will emerge and inspire others to feel included and welcome, and the landscape described here is proof of that.

__________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

1. Refer to “High Priests of Indian Electronica” from the May 2009 issue of Rolling Stone India for some background on these nights at https://rollingstoneindia.com/high-priests-of-indian-electronica.

2. Refer to “How Bhavishyavani Future Soundz Shaped Mumbai’s Nightlife” from the March 2014 edition of Rolling Stone India for more detail on this collective and their impact at https://rollingstoneindia.com/bhavishyavani.

3. The past few years has seen an influx of promoters forming, but the predominant agencies/promoters are OML, Krunk, UnMute, Submerge, Percept, and Wild City.

4. In 2016, a regular series of “properties” unfolding on rooftops, homes, and other arenas has begun to emerge – House Concert Delhi, BYOH (Bring Your Own Headphones), Living Room Sessions, Coral Sessions, an international franchise called Sofar Sounds – all of whom manage their own logistics and curation without the brokerage of agency, sponsor, or standard venue support.

5. The underlying reasoning for the series is outlined in an interview with the author at

https://www.redbull.com/in/en/music/stories/1331810936384/rana-ghose-on-forming-the-reproduce-listening-room.

6. Refer to “Music: Sounds of Defiance” at https://www.jabong.com/juicestyle/magazine/music-sounds-of-defiance.